For a long time, if you went to a library in Wilmington, NC there was one thing you weren’t allowed to research: the election of 1898. The story of the election of 1898 is still widely unknown.

Nonetheless, what happened in Wilmington radically changed racial politics in North Carolina.

The election of 1898 is the story of an American election, but also of something we don’t usually find in American history– the violent overthrow of a democratically elected government.

Wilmington leading up to 1898

In the late 1800s, Wilmington was the state’s largest city. It had a majority black population, (approx. 56%), and historians today describe it as a rarity in the post-Civil War south.

Wilmington represented what the new south could be in the 20th century– a place for black prosperity. The city had successful black entrepreneurs, doctors, teachers, and also black elected officials.

For a time, that was true throughout the state of North Carolina. North Carolina even sent four black Republicans to the U.S. Congress between 1875 and 1899.

In 1898, the Democratic and Republican parties occupied opposite parts of the political spectrum than they do today. Most African-Americans were voting for the Republican party, and the Democratic party was almost exclusively white.

Republicans in North Carolina were successful in part because of a third party, the Populist party. The Populist party was made up of mostly white farmers.

North Carolina Populists joined up with Republicans to form the Fusion Party. In the elections of 1894 and 1896, the Fusion party defeated the Democrats in sweeping victories state-wide. As a result, North Carolina now had a government that shared power between black and white politicians.

Together, they moved towards reforms that would favor black Americans and working-class whites.

Democratic party response

Reform was something that the Democratic party did not accept. Consequently, they started to make a plan for how to take back control of the state in the next election.

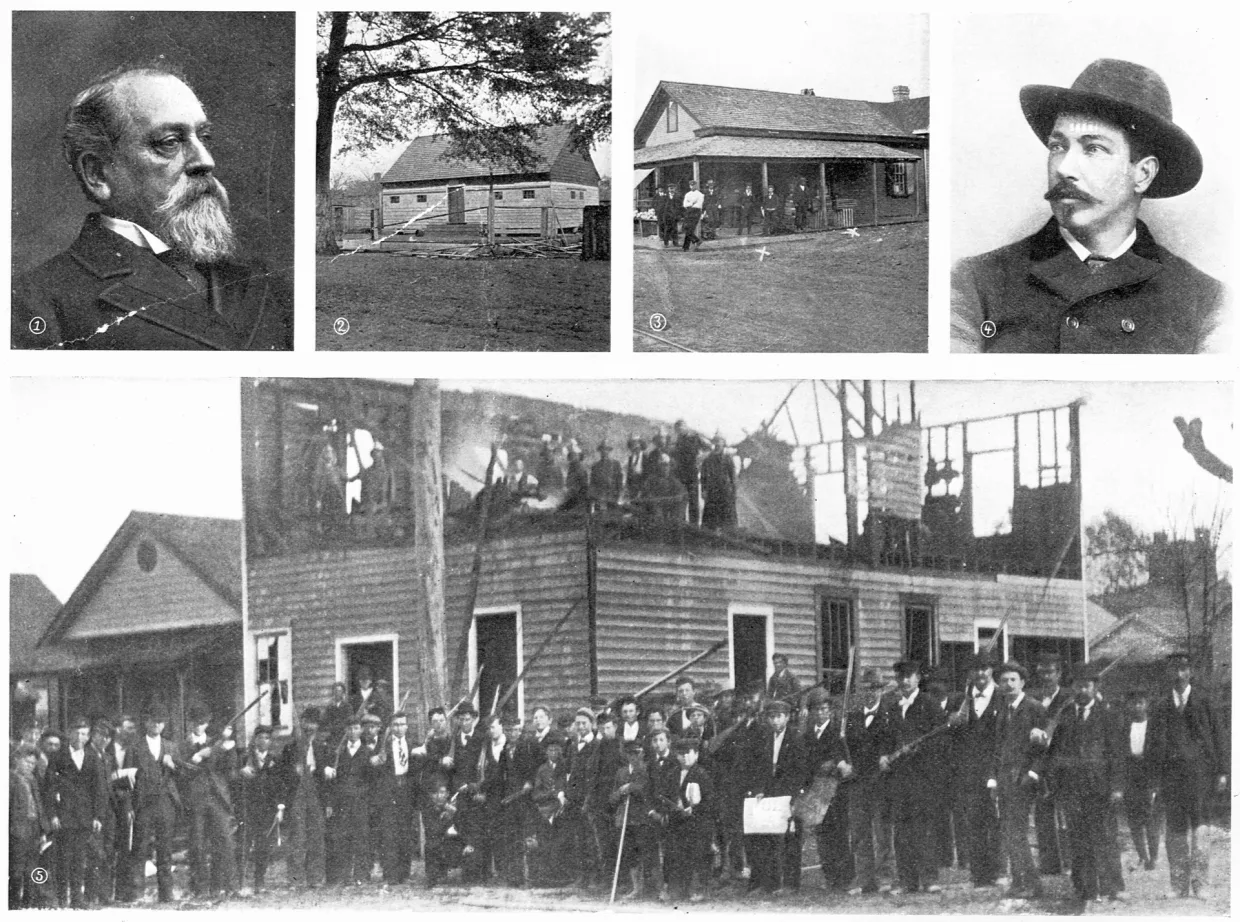

Party leaders like Furnifold Simmons, the 1898 Democratic party chair, Charles Aycock, future NC governor, and Alfred Waddell, a congressman, came up with a plan. To beat the Fusion party, they were going to lure white Populists to the Democrat party and away from their alliance with black voters.

Wilmington, with a large black population and a local Fusion government in power, would be a focus of the Democratic party’s campaign.

The Democratic Handbook of 1898 laid out their goal: to consolidate the white vote by stoking anger and resentment.

The handbook said, “this is a white man’s country and white men must control and govern it.”

The role of the news

The Democrat’s most effective tool was the media. One of North Carolina’s biggest newspapers, The News and Observer, was a Democratic party mouthpiece. It ran racist political cartoons throughout 1898. Not everyone was literate in 1898, but everyone could see a cartoon and understand it.

Many of the cartoons were centered around the threat of “negro rule,” even though the Fusion government was mostly white. UNC has an exhibit on the election of 1898, where you can see examples of these cartoons.

The cartoons also played up another fear: black men threatening white women. This was all part of the North Carolina Democratic strategy, but it echoed the national racist rhetoric of the time.

In one speech that Democrats printed in a Wilmington paper, Rebecca Latimer Felton, a prominent writer, spoke out in favor of the widespread lynching of African Americans to protect white women.

Her speech prompted Alexander Manly, a Wilmington black man and owner of the black-run Daily Record newspaper, to respond.

Manly’s editorial just added fuel to the fire Democrats were setting. Newspapers reprinted it, calling it a horrid slander.

Election Day

By the time the election rolled around, Democrats had thoroughly intimidated the Republican party. The Democratic party had a paramilitary group, the Red Shirts, who attacked and blocked black residents from voting.

The election resulted in Democrats winning every seat that was up for election or reelection. However, some Fusion politicians still remained in power because their seats weren’t up for election.

Coup d’état and violence

The day after the election, at a gathering for white men in Wilmington, Democrats unveiled a document called “The White Declaration of Independence.”

The declaration stripped black men of voting rights, gave white men a large part of the employment previously given to black men, and demanded that Manly leave the city forever.

The next morning, hundreds of white men marched to the Daily Record’s office, but Manly had already fled for his life. The mob then set the Daily Record building on fire.

Simultaneously, 200 armed men walked into city hall, prompting the mayor and board of aldermen to resign. As they resigned, the Democratic party voted in new Democratic members.

Meanwhile, the mob grew to around 2,000 men, and the violence spilled into the streets.

Effects on North Carolina

The new officials in the government enacted Jim Crow laws. The Wilmington that represented the spirit of opportunity for the south going into the 20th century never returned. To this day, Wilmington still hasn’t regained its black majority population.

The election of 1898 marked an end of black political representation in the state. It took 90 years for North Carolina to elect its next black congress member, in 1992.

Over the years, NC textbooks struggled to accurately describe– or even mention– what happened in 1898.

Despite more recognition of this dark past today, North Carolina still hasn’t undone the legacy of this event. The names of mob members like Walter Parsley and Hugh MacRae are on school buildings and public parks in Wilmington.

Modern connections

What happened in the election of 1898 isn’t entirely confined to North Carolina’s past, though.

If you review the news from the past few years, you’ll see our state’s long history of political suppression. From voter ID laws to racial gerrymandering, we’re still slowly moving forward.

Past political suppression, education about this side of history is a national debate. The Texas Senate just approved a bill that limits how students learn about historic racism. As of right now, it stripped more than two dozen requirements to study the writings or stories of multiple women and people of color.

This legislation comes on the heels of the University of North Carolina denying tenure to Nikole Hannah-Jones, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, after conservative criticism of her work.

It can be easy to look back on the election of 1898 and think of it as a far away event with no bearing on today’s world. But, with all the political, educational, and racial divisions we see today, perhaps it’s worth taking a look back. The history of our state and nation greatly defines our future.

Hi! My name is Marie, and I am the editor-in-chief of The Mycenaean. I am also President of Model UN and President of Quill and Scroll Honor Society. I love whitewater kayaking and rollercoasters.