The History of Socratic Seminars

In the fifth century B.C.E, philosophers and teachers created the socratic seminar. Teachers, most prominently Socrates, use the discussion style as a new form of sharing ideas and information. Instead of learning ideas directly from the teacher, students could now learn from each other. Students used socratic seminars to see information from new perspectives, learn to build arguments and defend them from countering views.

The Students

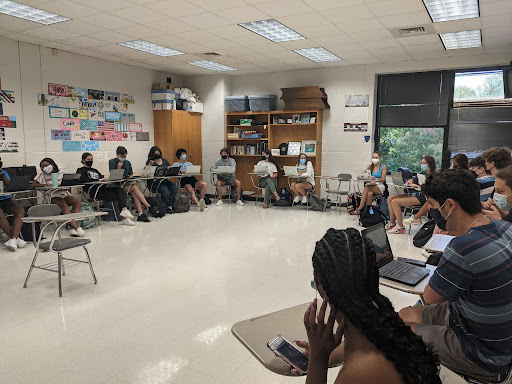

Socratic seminars are a tool almost every high school and college student are familiar with. Teachers all over the world use them to discuss everything from social issues to essays and novels, but what makes them so special? Why have they stuck around for thousands of years, and why do we use them in class today?

Julia Thorne is a sophomore at Leesville Road High School. As a Freshman, she took Paideia English and Social Studies. These two classes are only offered to first year students. They follow a traditional English curriculum, while delving deeper into texts and social issues by utilizing socratic seminars.

Thorne recalls how paideia helped her build confidence. “It’s really good at helping us build communication and sort of like helping us learn public speaking, it helps with social anxiety,” she said.

In addition to the skills she learned in her Paideia class, she also recalled how frustrating it was when trying to speak.

“I don’t like how it’s kind of competitive, how you have to keep fighting to speak and if one person speaks for the entire time you don’t get a good grade for it,” said Thorne

Other students faced similar problems when faced with their first socratic seminar. Ellie Bruno, a freshman at NC State and is well versed in the art of the seminar discussion–as a freshman in highschool, however, she definitely was not.

“My first couple of seminars freshman year of high school were horrible. My social anxiety was through the roof, and I couldn’t get a word in edgewise throughout the discussion. I quickly realized from my failing grades that I would need to step up and be louder,” said Bruno via text.

With some help, Bruno found her voice. She became more comfortable with seminars and eventually even learned to enjoy them.

“As for if I like them in the classroom, I personally do. Yes. I still get a lot of anxiety from them, but at the end of the day they are incredibly helpful. It really shows you that nobody has the same take or opinion on one topic, and trains you to be more open and how to stand your ground,” she said.

Teachers who implement socratic seminars into their discussions often innovate the ancient discussion technique in order to better fit their classroom and their students. They plan seminars to give everyone the opportunity to speak and encourage everyone to share whatever is on their mind.

The Teachers

Mr. Dinkenor, is a Paideia World History teacher at Leesville. In his seminars, he chooses to emphasize talking over annotations and planning. “ [I] made a big chunk of the grade a talking component,” said Mr. Dinkenor.

Like him, many teachers who use seminars grade mainly based on the amount of time spent talking in addition to the quality of the points made.

Teachers tend to grade seminars so a student gains the most points possible from speaking a recommended amount throughout the discussion–usually between three to five times. If one does not speak enough or over speaks they lose points off their grade for over contributing or not sharing enough with the class.

Another way teachers are changing seminars to better fit their classroom is by emphasizing smaller, more easily spoken in groups over one class wide discussion.

“I’ve found the fishbowl seminar to be really effective; students are assigned a partner, and during the first round, one student observes their peer who is speaking and provides them with feedback. Then the students switch roles, and the observer becomes the speaker. This way there is a smaller group discussion, and yet everyone is held accountable,” said Mrs. Price, an English teacher at LRHS via email.

Price teaches AP Language as well as English Three, using seminars in both classes. Discussion topics for the seminars include everything from poetry and fiction to films and even artwork. Price uses seminars not only because of the skills they help students develop but also because they completely deviate from the usual ways of teaching and testing.

“Seminars offer students the opportunity to demonstrate their learning in a completely different way than on a traditional pencil-and-paper test, “ said Price. “True Socratic Seminars are entirely student-led, and everyone has an equal stake in it.”

Socratic Seminars in College

In college, seminars are a different ball game compared to the high school seminar experience. The discussions act as a day to day event — a participation grade– as opposed to the high stakes quizzes and tests that they are in high school.

Marie Cox, a former Leesville student, is now a freshman at Saint Michael’s College in Vermont. This liberal arts school is known for holding small and interactive class discussions instead of the traditional large lectures seen in larger colleges across the U.S..

“At my college, a seminar happens every class session if you’re in a seminar-based class. It’s not some special event that’s for a grade. In my anthropology class, we sit in a circle every day and discuss readings and videos and ask each other questions. It’s not a scary thing because that’s literally all the class is,” said Cox via text.

Socratic seminars teach students skills they could never learn from your textbook lecture or test. They teach people how to build arguments, communicate ideas, and speak in front of their peers all the while.

“You can listen to a lecture and take notes, but you aren’t really engaging with what you’re learning about. Seminars are a way to push your thinking and challenge your peers’ ideas and understandings,” said Cox.

Hi! My name is Lauren! I’m President of the LRHS book club. Outside of school I’m a curler for Team Taylor and I like to rollerblade.