It’s unclear exactly when witches came on the historical scene, but one of the earliest records of a witch is in the Bible. From there, the concept of witches and witchcraft has taken quite the journey. (Photos in public domain)

The fascinating figure of the witch has long represented our society’s complicated attitudes towards female power. When contemporary society looks at on-screen witches through the decades, they can see some recurring traits.

A witch is an outsider, by choice or against her will. The witch often exists on the margins of her society. If she chooses to assimilate into the mainstream, her greatest challenge is reconciling her differences in a world full of normal people. If the witch does have a social circle, it usually consists of other women– her coven.

She has magical powers like the ability to fly, cast spells, shape-shift, or transform people. The witch uses all this mysterious knowledge to exert her will upon the world. Thus, she represents a departure from the stereotype of the helpless, submissive woman.

In her archetypal form, she is not conventionally attractive, and her ugliness is a reflection of her inner character. Yet, she’s also deeply vain: expressed through an obsession with making herself young and beautiful.

She’s almost always unmarried and hates children. In fact, children are often their primary victims.

“Witches are women whose embodiment of femininity in some way transgresses society’s accepted boundaries—they are too old, too powerful, too sexually aggressive, too vain, too undesirable,” writes Jess Bergman, Literary Hub’s Features Editor.

People have long persecuted the witch due to her transgressive personality. Her transgressive personality presents a fundamental question: Is there something wrong with the witch, or with the society that can’t accept her? Why is it that when a woman is confident and powerful people call her a witch?

Let’s dive into one of the biggest tropes that defines movies, T.V., and pop culture.

Characterization of the witch

Today, the witch falls into the same category as other supernatural and fictional Halloween characters. Throughout history, though, the idea of the witch has provoked fear and panic, often leading to the executions of those accused of witchcraft.

Witchcraft’s history

Real-life witch hunts sprung from periods of hardship: crop failure, bad weather, uncontrolled disease spread. These hardships lead communities to hunt for someone to blame. Historians today even link the Salem witch trials to economic deterioration, a harsh winter, and food shortages.

Still, that’s not the whole story. Blaming witchcraft for misfortunes is only half of it — the witch herself embodies various cultural worries specific to women.

As Roald Dahl wrote in his novel The Witches, “A witch is always a woman… There is no such thing as a male witch.” Various novels and T.V. shows portray witches as appearing to be ordinary people, looking like ordinary women.

The same sentiment was at play hundreds of years ago, in the Malleus Maleficarum, a 1486 treatise on witch-hunting. According to The Encyclopedia of Witches and Witchcraft by Rosemary Ellen Guiley, it was second only to the Bible in popularity– selling more copies than the Bible until 1678.

The definitive text boasts misogyny, arguing that women are inherently deceptive, wicked, and more prone to witchcraft because they are feebler than men in both mind and body.

Since men primarily controlled stories and news 400 years ago, they created the witch as an enemy– as a manifestation of their fear of women and fear of losing power to women.

Fears surrounding witches: knowledge

Witches continue to speak to the fear of certain behaviors in women, starting with our culture’s fear of female knowledge or intuition.

Look at one of the earliest popular representations of witches: the Weird Sisters of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Many critics have noted that the three witches resemble the fates of Greek mythology– three goddesses who spun threads that determined how long a mortal’s life would be, how much suffering they would experience, and how they would die.

In Macbeth, the Weird Sisters seemed to know how everything would play out. They strategically reveal information without ever giving the characters the full picture. In the end, Macbeth’s folly is thinking he understands one of their prophecies. This arrogance is what leads to his death.

Shakespeare’s tale offers an implicit warning: never assume you know as much as a witch. Witches have knowledge that puts them above everyone else. This power that they hold causes others to fear them, thus shunning them from society, playing into the witch archetype of being an outsider.

Powerful women could only ever be outsiders because Shakespeare, a man, created them. Powerful women were not normalized like powerful men. Rather, since these women had power and knowledge, the male author had to display them as dangerous outsiders.

Fears surrounding witches: children

Another common trait of the witch is she dislikes children. This characterization hits on something important. Female reproduction has always been part of the demonization of witches. The Malleus Maleficarum includes a section titled “How witches impede and provoke the power of procreation.”

This is an anxiety that manifests in both the old witch who’s clearly past child-bearing age and the hypersexual yet child-free witch. “The haggard witch and the sexy witch are the same threat: women not reproducing within the sanctioned family structure, or not reproducing at all,” writes Jessie Kindig, an editor at Verso Books.

But it’s not just that the witch has chosen not to have kids, it’s that she is more than willing to harm them.

Grimm’s Fairytales, published in 1812, features two witch figures. One being the Evil Queen in Snow White who uses witchcraft in a plot to kill her stepdaughter, and the second being the witch in Hansel and Gretel eats children.

Bergman notes that both women are “perversions of the virtuous and repentant mother.” Many stories drive this point home by casting the bad witch as a dark mirror of a more feminine, nurturing maternal figure. Think Wicked Witch of the West versus Glinda, Maleficent versus Flora.

Again, witches were created and controlled by male authors who believed that women fulfilled two roles: virtuous mother or wicked witch. The narratives they composed were based on the idea that women are shallow and unworthy of complexity. When a woman chose to not fit into the patriarchal status quo, they posed an open threat to men who held power.

Fears surrounding witches: vanity

On a different note, if people sexualize the witch, it’s often in the context of using her sexuality to manipulate men. This portrait is a stark departure from the witch’s male counterpart, the wizard.

Wizards are typically heavily desexualized– see Merlin, Gandalf, Dumbledore, or Saruman.

The Malleus Maleficarum spells it all out: “All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which is in women unsatiable… for the sake of fulfilling their lusts, they consort even with devils.”

Popular culture portrays the witch’s love or sexuality as overwhelming. In 2016’s The Love Witch, the romance-obsessed Elaine uses love positions on men. The potions lead them to be so overwhelmed with emotions that they’re driven to death.

The witch also defies societal expectations by having the gall to be ugly. Yet, she’s also characterized as vain, and this vanity is framed as inherently evil. As expressed by witches who try to regain their youth through violent means, like the Sanderson Sisters in 1993’s Hocus Pocus.

Meanwhile, stories where the witch disguises herself as young and beautiful evoke a fear of women using their appearance as a tool of deception.

Of course, the irony of villainizing the witch for her vanity is that not being young and beautiful is supposedly what makes her terrifying in the first place.

This fear and distaste for old age reflects a societal discomfort with age. In a world that worships youth, becoming old is terrifying.

Fears surrounding witches: power

Scariest of all is that the witch’s abilities make her extremely powerful. This open threat to the patriarchal status quo is often central to the witch’s story. It’s the very premise of the classic show Bewitched. After discovering that his wife Samantha is a witch, her mortal husband demands that she stops casting spells and becomes domesticated.

Interestingly, all these anxieties surrounding female power extend to non-witch characters, too. In Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, the villain of the story isn’t a witch but rather a young woman, Abigail, who spreads witch paranoia throughout her community. The nefarious Abigail still embodies several witch-like qualities: aggressive sexuality that effectively destroys her lover and his family, an unusual ability to manipulate those around her, and a callous disregard for human life.

In Macbeth, Lady Macbeth may not technically be a witch, but she displays an unquenchable thirst for power and is ruthless in obtaining it. As a childless, overly sexual woman she distances herself from femininity in motherhood, so she can dedicate herself completely to evil. She even implies that she would murder a baby to further her goals.

More importantly, men wrote Macbeth and The Crucible and created these witch-like women, reinforcing the role men play in constructing a narrative against women. From the Malleus Maleficarum to modern literary works, men have been the ones designing stories painting powerful women as evil.

In real life, people accuse others of witchcraft when they feel powerless. When they feel like a woman is exhibiting more power over them, not listening to them, or exerting their will upon them.

The attributes we associate with the witch aren’t rooted in the fear of the supernatural. These attributes are based on the fear of any woman who does not follow the traditional expectations of her sex. After all, all “historical” witches are fictional, created out of a distrust of women.

The Misunderstood Witch

The longtime villainization of the witch conceals a dark truth. Those accused of witchcraft have historically been victims, not villains. In real life, those accused of witchcraft have typically been the most vulnerable members of society.

During the Salem witch trials, the first three women accused of witchcraft were Sarah Good, an unpopular homeless beggar; Sarah Osborne, an invalid outcast; and Tituba, an indigenous slave. In other words, these were disempowered women who already stood out to the Puritans. Their differences from a traditional female figure in the Puritan society scared men, causing them to be seen as an “other”, which made them easy scapegoats.

In recent years we’ve started to see increasingly empathetic depictions of witches. The depiction of strong women as witches has changed. Society began to recognize women as complex humans who can be powerful and loving, educated and motherly, empathetic and strong. The idea that witches are not dangerous, hateful, and manipulative shifted because society no longer saw women as dangerous, hateful, and manipulative.

Some modern retellings of witch stories revisit iconic characters previously presented as one-dimensional. These movies give characters backstories, motivations, and a character arc.

The stories reveal how much a narrative changes when it’s seen through the witch’s eyes, rather than the community that shuns her. They openly interrogate the culpability of the witch’s society.

In her youth, the witch may have faced the shame of being different. Self-hatred drives her to live up to the world’s expectations of her.

Or, a formative trauma may lead her to resolve to become all-powerful as a means to heal the scars of disempowerment.

2014’s Maleficent shows its title character, who is technically a fairy but fits the witch criteria, as a strong, good young woman. Maleficent simply wants love, and therefore she makes mistakes throughout the film and expresses regret for her mistakes in a deeply human way.

2015’s The Witch reveals how the tendency to misunderstand witches can even extend to a woman’s own confusion about herself. After Thomasin’s family leaves their Puritan colony behind, they endure a series of strange phenomena. They blame Thomasin for these events, conflating her sexuality with wickedness and casting her out.

Eventually, Thomasin dedicates herself to the devil, joining a coven of witches. The film poses an interesting question: Was her family right about her all along, or did their cruel treatment force her to have no other ally but the witches?

As Glinda says, in the Broadway musical Wicked, are people born wicked or do they have wickedness thrust upon them?

These stories present being a witch as an appealing alternative to continuing on as a victimized woman trapped by society. Our most villainous portraits of the witch imply that she’s what’s wrong in a morally pure world, but looked at in another way it is often the opposite.

Society’s dysfunction and hypocrisy provoke the evil within her. Harnessing her full power– even if it causes harm– seems reasonable. Being wicked in a world that treats her wickedly seems logical.

The Witch Today

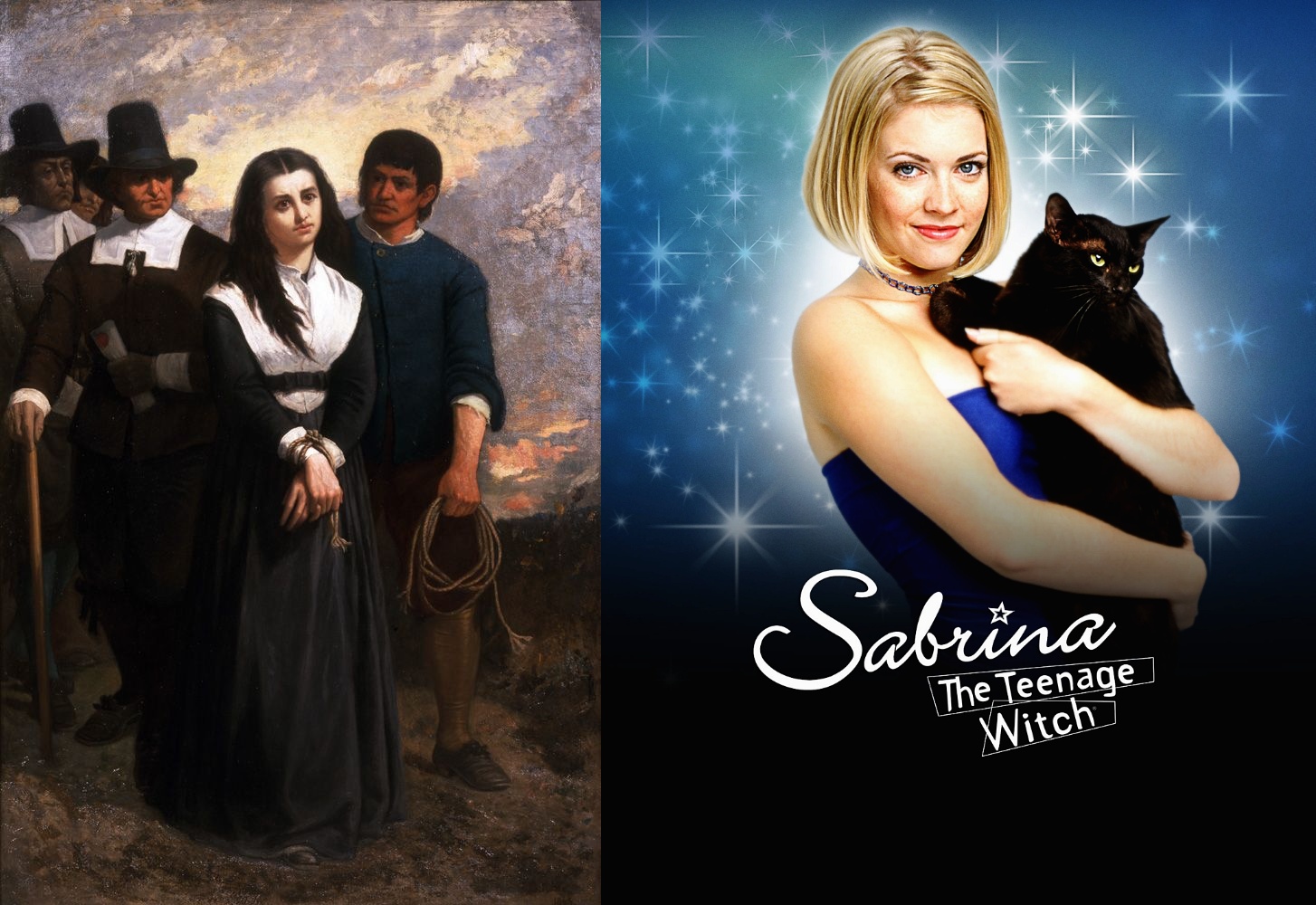

After many years of villainization, the witch has become a mirror that all women see a bit of themselves in. How did we get all the way from the Wicked Witch of the West to Sabrina?

We can see the trend of the relatable witch as early as 1942’s I Married a Witch, and 1958’s Bell, Book, and Candle up through the T.V. show Bewitched. All of which normalized the character and gave her the rom-com treatment, focusing on the humorous misunderstandings that arise from loving a mortal man.

1971’s Bedknobs and Broomsticks frames its witch character as a loving friend and eventual adoptive mother to children. It shows her using her powers to do good.

These stories suggest that outdated stereotypes are the root of most superficial ideas about witches.

The Harry Potter series made sorcery fun and desirable, cementing the witch’s normality. As Jess Bergman notes, “In Rowling’s series, practicing the Dark Arts is not a particularly gendered affair.”

Rise of the Teenage Witch

Making the witch more relatable goes hand in hand with the rise of the teenage witch. Rather than tales of horror, these are stories of fantasy and wish fulfillment. Young women use their powers for light-hearted fun.

Modern society is responsible for this changed narrative surrounding witches. Today, women and men are more equal than ever before. Therefore, authors and directors see no need to stereotype powerful women as frightening.

New depictions of the witch are meaningful allegories for coming of age. The teenage witch doesn’t have complete control over her abilities yet. Becoming the best witch she can means discovering the best version of herself.

Most significantly, the teen witch story shows a girl reckoning with her unique strength in a world that often makes her feel weak.

In Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Willow starts off as a shy wallflower before her abilities transform her into a confident woman who fears no one. In the series finale, Willow even uses her powers to empower other women.

In 1996’s The Craft, four teenage girls form a coven and use magic to take back their agency after feeling helpless. “Suddenly, a teen girl isn’t someone to be protected by men; she’s someone they need to fear,” writes Sinead Stubbins, a film critic.

More broadly, in recent years the witch has become an increasingly mainstream feminist symbol. Around 2016, the line “We are the granddaughters of the witches you weren’t able to burn” from Tish Thawer’s 2015 novel The Witches of BlackBrook began appearing on signs at women’s march protests.

The Wing, a women’s co-working space, announced: “we’re a coven not a sorority” on Instagram.

Interestingly, this coincided with the revival of the term “witch hunt” in the #MeToo movement. Men tossed the term about when complaining that they were being unfairly persecuted by the very women they’ve oppressed and marginalized.

As always, it comes down to fear. This time from those who worry that their own power is no longer enough.

Ultimately, witches have never existed. The witch is simply a metaphor — a character manifestation of a powerful woman who men fear. The stories of yore stereotyped and scapegoated women, an easy target in a male-dominated world. With a shift in equality among men and women, the need to villainize strong women has diminished.

Part of why female empowerment movements embrace the witch is that she embodies a message many young girls aren’t used to hearing. The message that there isn’t anything wrong with wielding power. The witch, to them, represents taking back the control that past generations’ fear stole from women.

The witch is no longer an enemy posing a threat, but a person embracing their potential.

Hi! My name is Marie, and I am the editor-in-chief of The Mycenaean. I am also President of Model UN and President of Quill and Scroll Honor Society. I love whitewater kayaking and rollercoasters.